dea what this type of genre is called. This genre is called film noir and it is a “visual legacy” that transformed from German expressionism, a movement in the 1910’s – 1920’s in drama and film, into what we know of today. However at the time that these films were being created, the directors did not actually know that they were creating a completely new genre of film.

dea what this type of genre is called. This genre is called film noir and it is a “visual legacy” that transformed from German expressionism, a movement in the 1910’s – 1920’s in drama and film, into what we know of today. However at the time that these films were being created, the directors did not actually know that they were creating a completely new genre of film.Aside from the visual aesthetics of the film, an audience usually has a decent idea of how the plot is going to begin and unfold. The plot focuses on a detective who is a man of honor and integrity who will always fight for true justice, even though it means they never move socially upward. He encounters many things throughout the film, especially the attention of a mysterious female character who is deeply implicated in the conspiracy. The film usually ends with the detective being able to solve the case, but is not changed by it in anyway. He returns to his life of obscurity, waiting for his next assignment.

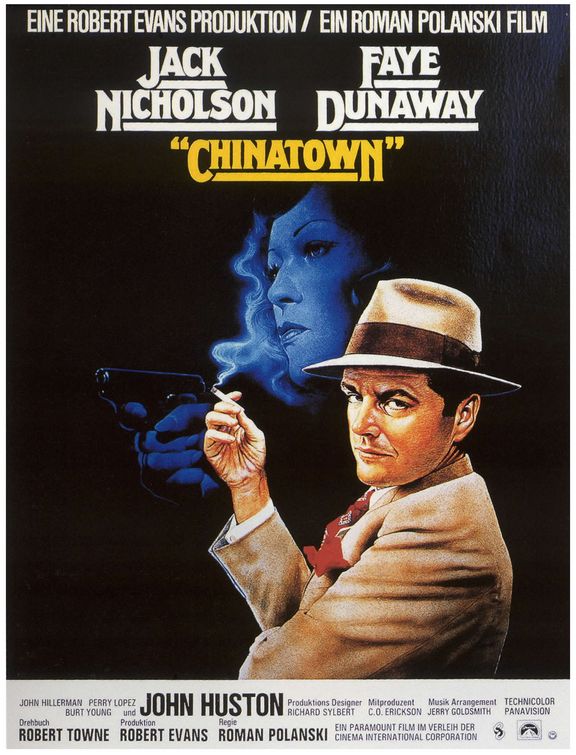

When we first look at the film Chinatown, a film set in the 1930’s that was actually shot in 1974, we automatically start think that the film is going to follow the prototypical outline that all films of this genre are going to follow. All of the qualities are there, besides the fact the film is in color. You have the detective, the darkness, the ambiguity, and a crime. However, Chinatown is not like any film of this type of genre. Both the charac

ters are nothing like prototypical archetypes of the genre. The characteristics of the character played by Jack Nicholson are different from what you expect a private eye to be. Instead of being a moral gentleman at the end, he instead does not solve the crime in the end. The female character, played by Faye Dunaway, is also different from what we expect. Instead of being an independent and courageous woman, she is someone that puts up a visage to hide anguish and ambiguity.

ters are nothing like prototypical archetypes of the genre. The characteristics of the character played by Jack Nicholson are different from what you expect a private eye to be. Instead of being a moral gentleman at the end, he instead does not solve the crime in the end. The female character, played by Faye Dunaway, is also different from what we expect. Instead of being an independent and courageous woman, she is someone that puts up a visage to hide anguish and ambiguity.I believe that these evident characteristics are not a mistake made in the film, but are an updated view of film noir. When the prototypical characteristics for film noir were made, society was at a completely different place than where it was when Chinatown was made. The sexual innuendos that were said in the 1920’s and 30’s were something that has become common in films in the 70’s. The depth of character is change that resembles the change of the film from the archetype of black and white to color. The characters in Chinatown are infinitely more complicated than the characters in most of the films that were made in the 1920’s and 30’s. This juxtaposes the depth of characters in the black and white films where distinguishing between the characters was as easy as looking at things in black and white.

As film technology starts evolving, so well the genres of film. No longer will one genre of film be able to tackle certain ideas. An action film will no longer just be seen as an action film. A thriller will now be able to touch on ideas that are pressing issues in our society. A slasher film could potentially make political critiques. As far fetched as this seems, one could only imagine how far fetched the ideas of the future of cinema people had in the 1920’s.